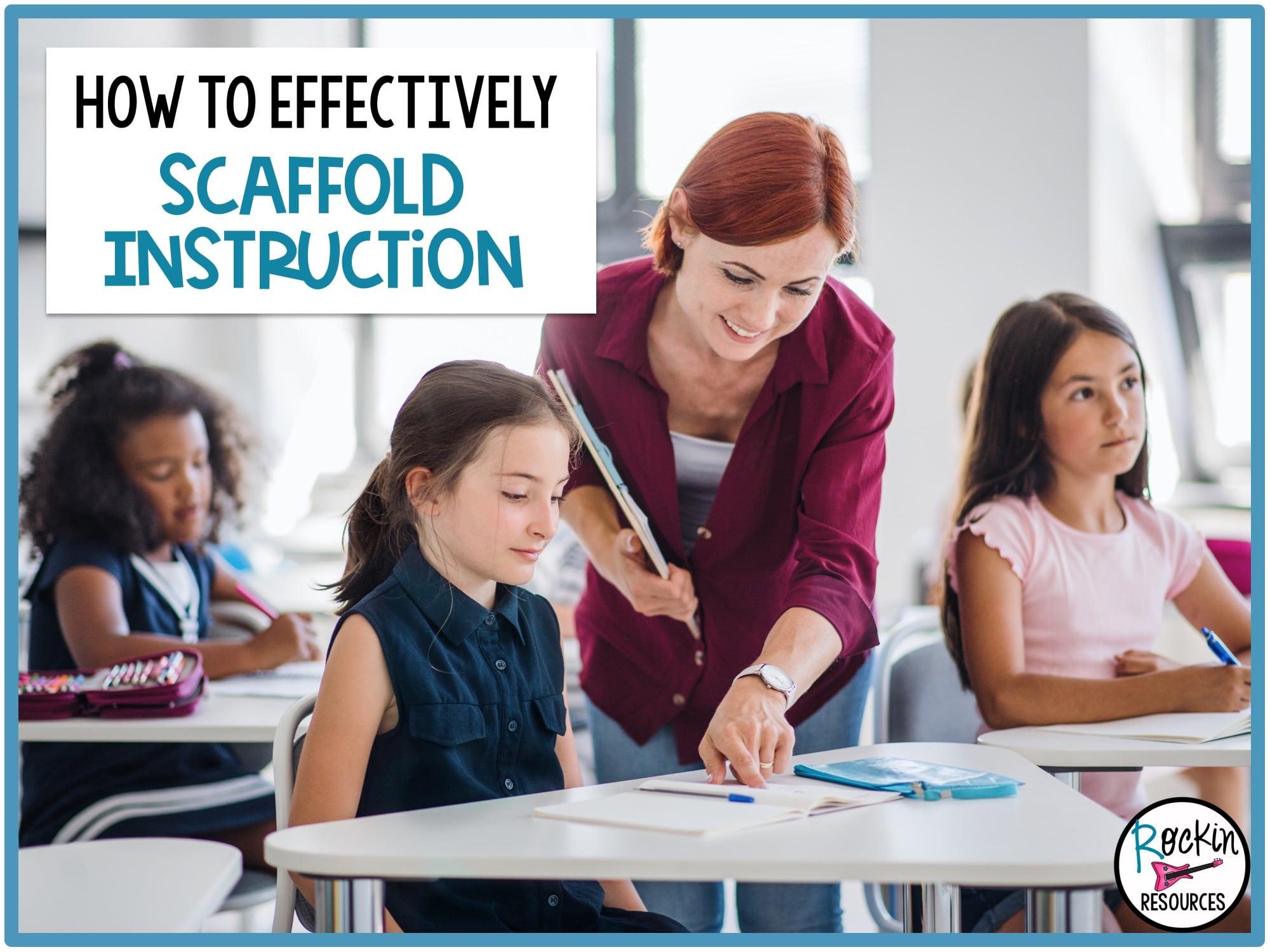

In this blog post, we’ll look at how to effectively scaffold your instruction and help students build increasingly sophisticated skills. We’ll also look at how you can help foster growth and independence through scaffolding.

Scaffolding and Differentiating

The methodology behind scaffolding is multi-faceted. Scaffolding can mean providing support and then removing it slowly. It can focus on creating greater independence. It can also be about students performing skills of higher difficulty. Be aware, scaffolding can look different in different contexts, but it’s not differentiation. Let’s say that you assign all students to read an article and then ask them to create a report on what they’ve read. In differentiation, students might read advanced articles, simplified versions of those articles, or be assigned completely different assignments instead of a report, such as a skit or poster. In scaffolding, on the other hand, you help students to complete the required task by supporting them in various ways, not necessarily by changing your assignment. Can you use both differentiation and scaffolding? Yes, but they are two different things.

Ladder of Skills and Ladder of Support

You can view scaffolding as both a ladder of skills and a ladder of support. A ladder of skills helps students climb up from a lower level—simple skills to skills with greater complexity. The ladder of support gradually helps students to gain greater independence. Both ladders ultimately lead to independence and greater competence. There is plenty of overlap between these areas!

Building Independence

A child can usually do more with support than they can independently. Just as you see a toddler standing while holding onto furniture before they are standing alone, scaffolding gives a student some support and then hopes to withdraw it to increase independence. What are some strategies to help your student build independence through scaffolded learning?

Fishbowl

In a fishbowl activity, the teacher or an expert student demonstrates the skill that students will be attempting. The expert is giving support by showing, not simply telling. For students who are visual and auditory learners, watching how something is done in multiple modalities is very helpful. After they witness this, they are more likely to be able to complete the task independently; however, as with all scaffolding, support should be made available if a student is struggling even after watching the demonstration.

Explicit Teaching: Teacher, Class, Group, Student or I Do, We Do, You Do

This is the gold standard of release of responsibility. There are many different ways to use this tried and true methodology. The basic premise is that the teacher begins a lesson by explaining and demonstrating exactly what needs to be done. Next, the whole class, with the teacher’s help, attempts the activity or problem. The teacher is there to support students and students support each other. Then, either a small group or an individual student tackles the problem or task. You may choose to divide this step up, providing struggling students with the option to keep working with a group and let students who are confident in the procedure move on to independence. As you can see, the lesson began with students taking zero responsibility and relying solely on the teacher. Over time, responsibility was released to the students and they no longer needed the teacher. They stood on their own as individuals. This method can be used with the simplest of tasks to the most complex, meaning it is more about gaining independence rather than simply increasing skill level.

Think Aloud

Students can often achieve independence with unfamiliar skills if you scaffold their thought process. A great way to do this is to showcase your own thought process—the process you need them to have—as you model a task. Talk your way through your thinking, demonstrating to students what they need to do once the ball is in their court. I talk about modeling all the time with writing. It is so important to talk through the brainstorming step of the writing process, so students can hear your thought process. Then when you model each mini-lesson, students can see what you expect from them in their writing.

Collaboration and Peer Practice

There are dozens of ways to help students, and one way is to have students help each other. In Vygostsky’s original explanation of scaffolding as a social learning theory, peers helping peers is fundamental. Working with peers can allow students to achieve what they can’t do alone. A teacher isn’t the only one who can teach and support. Assign students to work in small groups, with partners, or with a peer mentor or tutor. You can pair an “expert” with a novice, aware that the pairing will switch often, since everyone has different strengths.

Building Skill

A child can typically identify letters before they can read sight words. Students count before they add. Scaffolding to increase difficulty and complexity of skill focuses on giving students simpler tasks and building to harder ones. What are some strategies to help you scaffold students to start low and slow and end up flying high?

Have a Logical Framework in Mind

- When you start a unit, make sure students have background knowledge about key concepts. Activate background knowledge through a variety of ways, including picture walks, book boxes, anticipatory guides, KWL charts (Grab some free charts here), Notice Think and Wonder, concept maps, etc.

- Provide students the opportunity to practice skills that will be needed to accurately perform the new skill. I call this Step-by-Step Skills. For example, providing instruction and refreshers on adding, subtraction, and multiplication is necessary before starting division. Another example: when teaching theme, review story elements, main idea, summarizing, lessons, and topics prior to introducing the concept of theme.

Front-load Information

Begin with activities that will prepare your student to tackle something more challenging. Make sure that you front-load needed information, such as vocabulary and procedures so that the student won’t be hampered by lack of knowledge. Another example is brainstorming. In writing, provide word lists for students to guide their thinking. With this sort of scaffolding, you equip students with the right tools to master harder tasks.

Purposeful Questioning

Open a line of questioning when you introduce a new, more difficult skill. Suggest some questions students might have. Tackling questions that may come up as students are working before they begin will supply them with necessary information and pave the way for them to tackle the task more successfully.

Anchor Charts and Graphic Organizers

Provide anchor charts and graphic organizers as you begin explaining new concepts and skills. This will help students to have a guide in advance as they build their skills, using the concepts you’ve already outlined. These can be placed in notebooks for future reference.

Share Your Vision

Explain to students your “first, next, last” vision. For example: “First, you should be able to identify nouns in a sentence. Then, you should recognize verbs as the action that nouns do. Last, make your own complete sentences using a noun and verb.” By sharing your trajectory with students, you are able to help them realize how smaller skills will build to the larger achievements you desire.

No matter how or why you scaffold, support is the key. Whether you want to focus on greater independence or increased skill level, your students will need you to build with them and then release responsibility to them. Scaffolding can be done without any special equipment and with virtually any subject. Studies across the globe and across the decades have shown that scaffolding is highly effective. You are probably scaffolding on a daily basis because it’s the heart of being a guide and mentor to your students. If you feel that your guidance game can use a boost, hopefully this article has given you some ideas!

GO ROCK YOUR TEACHING!

What is the meaning of scaffolding instruction and the pedagogy behind it? Click HERE.